Innumerable books have been written about Toyota and their lean manufacturing practices. Literally thousands of companies have tried to emulate these practices, some with some short-term success, but most with little or no long-term success. Jeff Liker, author of The Toyota Way, at one point estimated that only about one percent of US companies are truly effective at applying lean manufacturing practices. Few achieve the high level of sustained performance embodied in lean manufacturing principles. Why is this?

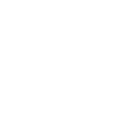

There are a multitude of reasons, but one need look no further than the Toyota House, which is a visual model depicting lean manufacturing principles. A simplified version of the model proposed by Jeff Liker in his book, The Toyota Way, is shown in Figure 1.

Now let’s ask the question, “Are you ready to apply Kaizen / Lean manufacturing?”

Before we continue, let’s note that Just-in-Time has to do with having the right part, at the right time, in the right amount, while running the plant steady according to a particular pace or rate, and having continuous flow, where you use a pull system to make to demand. It also incorporates quick changeover for minimizing inventory requirements, while managing the use of equipment and integrated logistics. In-station quality has to do with things like making problems visible, stopping the process for any problems with quality, error proofing, and solving problems to root cause using simple techniques like 5 Whys.

I. The Foundation – Long-Term Thinking, Employee Engagement, and Process Mapping.

Of course any good strategy is built on a solid foundation. So, let’s begin there, and ask some additional questions:

Long-Term Thinking. Is your company one that is characterized by long-term thinking, even at times at the risk of short-term profit? Or, alternatively, are you almost totally focused on short-term profit, even at the risk of your future? Granted, you must cash flow the business in the short term. And, if you’re publicly traded, meeting your quarterly goals and analyst’s expectations are really critical to your share price. But is your company willing to occasionally miss a given quarterly forecast if it means longer-term growth and profit? Of course you wouldn’t want to do this, and you may not have to do this, but would you be willing to do it? Just for argument’s sake, let’s give ourselves a score, with a 10 being that we’re very willing and have, though rarely, actually sacrificed short-term profit for long-term gain and have actually realized the anticipated gain by making that decision. A zero means we’d never do that and are almost exclusively focused on this week, month, or quarter. Yes, we have one-year and five-year plans, but those are hopes and dreams, and we don’t pay them much attention when we run into a slight bind in meeting quarterly estimates. Most companies, I think, will be somewhere in between. Give yourself a score.

1.Process Mapping. Do you routinely map your processes (production, engineering, maintenance, marketing and sales, procurement, accounting, etc.) to understand how things happen in your company, where you’re incurring waste, and where you’re adding value? Are you encouraged to think at a systems level regarding the impact a decision in one area has on another area and on the entire business? Let’s give a 10 to those who do this well and do it routinely, and a zero to those who don’t do it at all. Most will be in the middle somewhere.

2.Employee Engagement. Do you have various processes for engaging your employees? For example, do you have routine structured improvement time, using the appropriate tools for that improvement (tools like kaizen, 5S, 5 Whys, RCM, TPM, and so on)? Are people fully trained in these improvement processes and tools? Are your employees fully trained in their jobs, including requiring specific demonstration of the skill to do each task before going to the next level of skill? Is there a personal development program for each employee? Has it become a routine expectation that they will be called upon to do problem solving? As I’ve always said, if you want to know where the problems are with the work being done, ask the people doing the work, and get them to help you improve the work, and you’ll get ownership and so-called engagement. Let’s give a 10 to those who are doing all these things exceptionally well, and a zero to those who aren’t doing any of these things. Give yourself a score.

II. The Next Level – Stable, Standardized Processes.

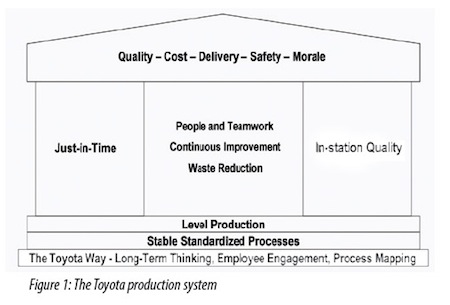

To apply the principles of just-in-time, having the right part, at the right time, in the right amount, you must have stable, standardized processes. Stability of course would include equipment reliability. Otherwise, you’ll need lots of inventory and other counter measures to compensate for the instability in your system. Figure 2 provides a model that we’ll use to describe various issues around stability.

In this model, production flow is going to the right, while demand flow is coming from the left. Balancing precisely the variability of production flow with the volatility of demand flow is difficult at best. A lack of product to deliver in a timely way can result in lost sales and profits and/or unhappy customers who seek other suppliers. Too much product represents waste in the form of excess inventory, working capital not working, and that same inventory incurs additional inherent costs for storage, potential damage, hidden defects and scrap, deterioration with time, and so on.

In between processes we often have delay times for one reason or another. For example, it may be that upstream supply has been disrupted because a process has unexpectedly failed, or an operator didn’t show up for work, or there are raw material problems related to quality or quantity. For many of the same reasons, it’s also likely that we have inherent variability in each individual process in terms of daily quality output from that process. Note the variation in daily output for each step in the process shown. Top all that off with several different products, or so-called stock keeping units (SKUs), and it results in lots of complexity to manage and still meet a typically volatile customer demand. We manage all these delays and variability by keeping buffer stocks: extra raw material, work-in-process (WIP) between processes, and finished goods, along with extra spare parts, overtime, extra people, and so on. The greater the variability, induced by lack of stability and equipment unreliability, the more counter measures that are needed, and the less likely it is that you will be able to use the just-in-time approach. Indeed most folks are in the “just-in-case” mode, because they don’t have stability.

Some have decided to expose these problems by reducing inventory, to “expose the rocks” so to speak, only to then run squarely over the rocks and nearly sink the boat. It’s important that we take a balanced view on the reduction of inventory. Some problems are known to us without having to reduce inventory. For example, if production planning changes the production schedule daily, or even shiftly, to suit sales demands, or if equipment and process failures occur frequently, we should not reduce inventory before addressing those problems. We also need level flow in production, a key lean principle. As we address those problems, we will get better stability and can confidently reduce inventory and still meet demand.

So, how stable are you? How ready are you to support level flow and making to demand, and thus able to support lean principles? Let’s score ourselves on this one as well.

1.Production Planning. How often do you change the production schedule in a significant way, such that you require significant changes to raw material, equipment set ups, or inventory planning? Granted, this may vary with industry. For example, I would expect that discrete parts manufacturers would have more inherent changes because of their complexity in product mix. For argument’s sake, let’s give a 10 to those who have only one change per month, and a zero to those who have daily changes. Give yourself a score.

2.Variation in the Daily Production. What is your variation in daily production output? While there’s considerable variation in industries, for argument’s sake, let’s compare plan to actual. If your statistical standard deviation is greater than 10%, it would seem to me at first glance that you’ve got a serious problem and deserve a zero. If it’s less than 1%, you’re really quite good. Give yourself a score.

3.Quality. What is your quality rate? Once again this will vary from industry to industry, but for argument’s sake, let’s give a 10 to those who have six sigma quality (less than three defects per million units produced), and a zero to those who have more than 30,000 defects per million.

4.On-Time Delivery. What is your on-time delivery performance? Let’s say that anything less than or equal to 80% deserves a zero, and that 100% deserves at 10. Give yourself a score.

5.Inventory Turns. What is your inventory turns ratio? If you don’t know what this means, that’s a different kind of problem. Ask accounting, and ask them why it’s so important. The more inventory you keep (a lower ratio), generally the more unstable your production system. The higher the ratio, the more stable your system. So, again for argument’s sake, let’s give a zero to those whose inventory turns are two to three, and a 10 to those whose are over 50. This too will vary from industry to industry, so adjust this as you see fit. Give yourself a score.

6.Unplanned Equipment Downtime. How much unplanned equipment downtime do you have? Anything around 1% or less is really good, indicating high equipment reliability, and deserves a 10 (or a nine anyway), and anything over 10% deserves a zero. Give yourself a score.

7.Reactive Maintenance. Related to unplanned equipment downtime is reactive maintenance. Reactive maintenance is defined as work you did today that you didn’t plan to do at least a week ago. Schedule break-ins would be another measure of reactive maintenance – how often do you change your scheduled work in a given week? What percentage of your maintenance is reactive? Anything less than 10% is really good and deserves a high score. Anything more than 50% is really bad and deserves a very low score. By the way, another measure here might be emergency maintenance, where anything less than 1-2% is quite good, and anything more than 10% is quite bad. Give yourself a score.

Finally, as noted, you should feel free to modify the criteria we have suggested to suit your particular circumstance, even adding additional criteria. So, with your scores and your overall review of this, what do you think? Are you ready for a lean manufacturing / Kaizen initiative? Or should you get back to basics, focusing on getting stability in your processes and equipment and engaging your employees in problem solving and process mapping, all the while thinking a little more long term?